On the far western edge of Mongolia, in the Altai Mountains of Bayan Olgii aimag, a national park nudges the border with China. This place is called Chigertei (Чигэртэй), although it is sometimes spelled Chikhertei (Чихэртэй), which is how I read and wrote it for the few months between first hearing about it and actually setting foot there. The g-versus-kh debate is a reminder of the region’s unique cultural dynamics; the majority of Bayan Olgii’s population is ethnically Kazakh, descendants of a small number of refugees who settled in Mongolia during various 18th and 19th century conflicts with the Russians and Chinese. In 1940, the socialist government of Mongolia formed Bayan Olgii as a Kazakh aimag, creating a place where Kazakhs were allowed to maintain traditions that were more harshly curtailed in Kazakhstan itself, which was then part of the Soviet Union. Following the advent of democracy in 1990 and the opening of Mongolia to the wider world, some of these traditions became world renowned. Eagle hunting and the richly embroidered Kazakh ger hangings made for weddings are synonymous with the region. Although all official business in the aimag is conducted in Mongolian, school is taught in Kazakh, Kazakh remains the language of everyday interactions, and many families in more remote regions don’t speak much Mongolian at all. Bayan Olgii is a region where Mongolian and Kazakh run up against each other, culturally and linguistically, in interesting ways.

This is the source of the Chigertei/Chixertei mashup. Chixer means “sugar” in Mongolian, and Chixertei, roughly translated, means “sugared,” which, as a Mongolian speaker, I took to be a poetic reference to the snow that girds the Altai peaks for most of the year. Chigertei, on the other hand, means “a one-eyed two year old horse” in Kazakh. A long time ago, my Kazakh counterpart from the park administration told me as we jolted along the road to the park, there was a one-eyed two year old horse that hung out in the valley, and that’s how the place got its name. Why do Kazakhs have a specific word for a one-eyed two year old horse? Are there a lot of one-eyed horses running around Kazakh-populated areas? Is there a different word for a one-eyed three year old horse? Mongolian is like this in its precision – there are verbs to describe a calf running around with its tail in the air, or the act of tying ribbons in a horse’s mane to designate it sacred. There are dozens of words to describe the colors of a horse’s coat, and a whole herd of words to describe yak-cattle hybrids depending on the generation of hybridity. There are several words for “friend,” some of which indicate a greater degree of affection and closeness than others. There are a whole set of verb tenses that you employ to indicate how recently something happened, and how certain you are that it actually happened if you didn’t witness it with your own two eyes. But with Kazakh, I had no idea where things get specific, because the sum total of my Kazakh skills could be summed up in the two most essential phrases in any language: “Thank you” (Rakhmet) and “Are there any wolverines around here?” (Kunnu bar ma?) The exchange on the road to Chigertei served as a reminder that I was on strange ground. I’ve worked in Mongolia for 17 years and I’m used to being agile and fluent, culturally and linguistically. It felt both off-balance and also exciting to be in a place where I didn’t know what was going on 100% of the time.

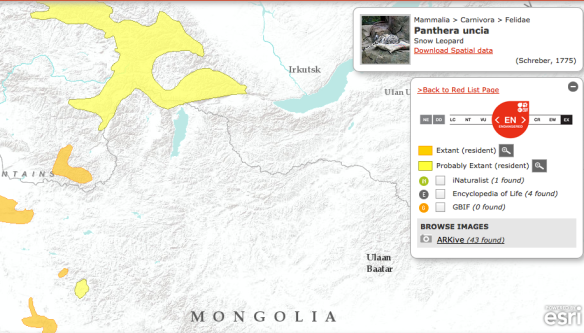

Whatever direction you take the name, Chigertei appears to be full of wolverines, and that was why I was there. In May, a colleague who had set up cameras for snow leopards in Chigertei contacted me to tell me that he had gotten dozens of photos of wolverines, and would I be interested in collaborating on a project? I’d been to the Altai before as part of my wolverine quest, most recently in 2011, to interview and collect pelt samples. I’d wanted to work there on a more extensive and systematic program, but hadn’t had the time to do the most laborious preparatory task for any wildlife work in Mongolia – setting up relationships with the various authorities and finding local counterparts who were interested in collaborating. Barry Rosenbaum, the wildlife biologist who had put up the snow leopard cameras, had already done that work, so it was easy to agree. Easier still because snow leopards were my first wildlife love, the animal that had led me to the high mountainous landscapes that wolverines inhabit. Barry would be collaring in Chigertei’s sister park, Khokh Serkh, which meant that I might, if I were very lucky, have the opportunity to see an animal that held enormous personal significance.

Luck seemed to be in short supply for the first ten days after we set snow leopard snares in Khokh Serkh (the name, definitively Mongolian, means “dark blue billy goat” and refers to both the Special Protected Area and the mountain range encompassed by the SPA). The plan was to spend the first ten days of the trip collaring snow leopards, and then a week in Chigertei, 40 kilometers to the west, setting up baited wolverine camera stations. After a frigid first two days in the Khokh Serkh base camp, the weather warmed, and the Mongolians and Kazakhs insisted that the snow leopards would stay up high and away from our snares, snoozing in the sun, until the weather changed again.

Whatever the cause, the snares remained empty. The cameras we’d set up nearby yielded beautiful photos of ibex, quail, and ermine, but no sign of big cats. I was happy to be out on a snow leopard expedition, but it was mostly waiting, interspersed with the daily anticipation and letdown of heading up to the higher valleys to check the snares. The time between was spent rambling around the mountains, but there was something edgy and almost spooky about the steep, narrow, rocky valleys, dark in the scant light of the failing year. On one of our daily excursions to check the snares, my horse’s cinch strap slid back, the horse panicked, and I was thrown, dragged through a boulder field on a steep slope, and kicked twice. The damage was relatively superficial – bone bruises, a torn ligament or some other trauma in my right wrist, the most shockingly purple hoof-shaped bruise on my left buttock – but I couldn’t hike for a while afterwards, or sit on a horse, which meant several long days sitting in camp trying to figure out how to do anything useful when my only functional limb was my left arm. I was more than ready to get out of Khokh Serkh by the time we piled into the range rover and headed to Chigertei.

The land of sugar and one eyed horses was enchanting by comparison, a wide open swath of valley flanked by dramatic high peaks, the weather moving fitfully and spectacularly across the mountains and the river and the moraines left behind by recent glaciers, and wolverine tracks everywhere.

We stayed with one of the few families that winters in the valley – there are many more in the summer. The family were relatives of Yelik, our liaison at the park. His forebears had lived in Chigertei Valley for generations, he said, and pointed to a crumbling cemetery that we passed on the drive in, and said, “My family are all there. Two hundred years.” His cousin Yerlan, her husband Jaksalak, and their daughter Raya were our generous hosts, giving us space in their adobe house, renting horses to us, and regaling me with tales of wolverine sightings up and down the valley. For the first time ever in eight years of wolverine work in Mongolia, I heard stories of regular wolverine depredation on small livestock. Jaksalak told me, through translation into Mongolian by our ranger Aska, that he’d seen five wolverines together in the early summer, that he’d spooked them out of a thin line of forest that ran east-west along the north-facing slopes of the valley, and that they’d fled up into one of the big bowls above treeline. Five wolverines together could only be a family, and if it was a female and her kits-of-the-year, that meant she’d successfully nursed a litter of four. When I asked where they habitually saw wolverines, Jaksalak and two fellow herders waved their hands across the valley: everywhere.

It was pointless to speculate based on unverified stories, of course, but the herders of Mongolia know their wildlife well – far better than the Americans who report wolverines in their backyards and then send me photos of porcupines or foxes – so I was inclined to believe them. The photos from the snow leopard cameras showed at least two individuals visiting the same camera station within days of each other, and returning repeatedly. It was all very tantalizing. But we’d learn more only by doing some scientific documentation.

The first day out, back in the saddle for the first time since being thrown off, I had a hard time focusing on where I was, too busy clutching the reins and trying hard not to think about the horse slipping on the ice, kicking me, dragging me across boulder fields, snapping my neck. Then we came up over a massive moraine and stopped at a boulder covered in petroglyphs, and all the crowding fearful thoughts disappeared as we dismounted and looked at the animal figures chipped from stone ages ago. Aska opined that the figures were little wolverines; I thought they were ibex. They were probably from the Bronze Age, which, in Mongolia, extended from about 2000-1000 BCE. There are petroglyphs like this all over the country – very ancient ones showing woolly rhinoceros and ostriches and mammoths, more recent scenes of men in chariots and reindeer with the beaks of birds. Out of all of this vast, Pleistocene world, the wolverine remains like a talisman of a lost past.

Petroglyphs. Depending on which end you see as the head, you can imagine these as running ibex with curved horns, or open-mouthed, stripe-tailed carnivores.

We rode further up the moraine and came out into a side valley, walled in at its head by another jagged range of peaks. From here we went on foot up the valley, and then up an east-facing slope, walking carefully among the snow-covered large-boulder talus. Before long we crossed wolf tracks, and then, inevitably, the prints of a wolverine. They led up through the talus field onto the ridge, where they and the wolf tracks joined a well-worn game trail running along the crest of the slope.

We set up four cameras in that valley, all of them along the east-facing slope. The west-facing slope was sheer scree and bare of snow, steeper and higher, far less appealing as a travel route. Aska and Dukhai, another of the winter herders, guided the effort, choosing spots where they’ve seen wolverine tracks in the past.

That night the wind rose until it howled around the outside of the house. Inside, Aska practiced his English by reading aloud from the back issues of the New Yorker that I bring with me on these trips; his pronunciation was flawless, and after a a sentence or two he would tell me, in Mongolian, what he understood, and then I would explain where he’d understood correctly and where he’d gone wrong. Since it was the New Yorker, this necessitated trying to explain phrases like “pathologically incompetent president” and “hipster locovore Brooklynites,” which was both headache-inducing and also a welcome challenge to improve my Mongolian skills. Neither Yerlan nor Jaksalak spoke Mongolian, although Yerlan liked to order me to eat more of the various dishes she cooked, thus improving my Kazakh vocabulary by about 1000% in the space of 24 hours. At some point, I explained to Aska in Mongolian that the wolverine’s Latin name meant “glutton” and that it had a reputation for eating enormous amounts of meat; Yelik, overhearing this, explained to Yerlan and Jaksalak in Kazakh; and everyone began saying “Gulo gulo!” before digging in to whatever dish Yerlan put on the table in front of us. Most of the time this was besbaramak, the signature Kazakh dish, which involves most of a sheep or goat, boiled for several hours, and served with enormous flat noodles, boiled carrots and potatoes, and sometimes a side of horse sausage. Invoking the wolverine came shortly after we washed our hands and bowed our heads and lifted our palms up for a quick blessing on the food from Allah. Sometimes I ended up translating whatever I understood back into English for Barry, although I’m terrible at remembering to do this, because translation is a task that requires focus. Later that evening, Aska and I digressed from New Yorker-level topics into our mutual enjoyment of the show Vikings, discussed which characters we most liked, and chatted about Norse history and Kazakh history. There was more comfortably cosmopolitan code-switching going on in the confines of that little adobe house, under the howling wind in the remote Altai, than in any place I’ve been in a while.

The wind went right on howling, and when we got up the next morning, a blizzard was beating down on Chigertei. Aska and Yelik swore it wasn’t as bad as the snowstorm that had hit the valley a few weeks before, so with that in mind, we all put on our warmest clothes and rode out.

It could have been worse. It could have been a few degrees colder, the wind might have had an even sharper edge, the snow could have been thicker, the visibility even more curtailed. As it was, I could see the dim outlines of the near mountains, if I squinted into the wind and snow, and I could remind myself that I’d been far colder and more uncomfortable, once or twice, on the ski transect of the Darhad that I’d done back in 2013. It was tolerable, in other words, in the minimal sense of the word. We were riding further out that day than we had the day before, but over less tricky terrain. The conditions did not make the horse any less nerve wracking, and Yelik and I had a moment of mutual vocabulary-building when I explained that I was nervous about galloping the horse in icy and snowy conditions. “Nervous” was new to him, and I realized with shock that I’d never used that word in Mongolian before – how had I avoided having to learn it when I’d dealt with everything from ornery horses to psychotic and potentially rabid dogs to drunk herders breaking into my ger?

I saw almost nothing of the valley we reached, except for the sites where we set the cameras. Those sites emerged out of the blinding white as we stumbled towards them, knee-to-thigh deep in drifted snow, the whole landscape eerie and markerless. We left the horses behind near a stone wall enclosing a hay field or corral and waded upslope. These stations we baited with the flanks of a goat, roadkill not being an option in Mongolia as it was in the US.

Dukhai, Aska, and Yelik setting up a camera. They did 100% of the physical labor since I couldn’t use my wrist. They deserve all the credit in the world for the success of this trip.

For our pains, whatever powers exist out there granted us bluebird conditions the next day, which took us up the north-facing slopes and through the thin larch forest to the base of the massive north-facing bowls. Where these bowls narrowed, and along obvious wildlife highways running east-west, we set the last of the cameras, baited with the rest of the goat.

I stayed high up on the mountainside, walking back along the wildlife trails; Yerlan and Jaksalak’s home was perched beneath the slope several kilometers to the east, and, in a move that probably fooled no one, I pretended that wading through the deep snow at high elevations for all of that distance was super fun, because my horse – which was really Aska’s horse, he’d trained it from a colt – had been edgy all morning on the ride out. I was happy to turn him over to Aska and hike back.

I hit a set of wolverine tracks and followed it up into the trees, out of sight of the group of men riding their horses across the plain below. Suddenly there was yelling, a huge commotion from the men, ringing dimly off the trees. I’d followed the tracks far enough into the forest that by the time I came back out, all I saw was the group of them leading their horses back to the house. They were on foot, which was strange, but I thought that they’d gotten off for a smoke break. I arrived back maybe a half hour after they did, opening the door and ducking into the dim light of the interior, ready to prattle on about the exciting wolverine tracks, but everything inside was silent and heavy and the hair went up on the back of my neck.

Yelik shook his head and said, in English “Today was so scary.”

Aska was lying on the floor, on the rolled out thin mattresses on which they slept, and I remembered the shouting and knew immediately that something had happened with the horse. And it had; while I’d followed those tracks up into the forest, Aska had stopped to take a photo. He’d spurred the horse to catch up with the others, and the horse had hit a wind-scoured snow drift; his front legs had plunged into the snow, Aska had slid forward so that his boots jammed into the stirrups, and then slid off the right side of the horse. In Mongolia horses are freaked out by anything approaching on the right, including riders who slide down on that side. The horse bolted, dragging Aska at a full gallop for somewhere between 30 and 50 meters through a boulder field. He was kicked in the shins, just as I had been, before he got free of the stirrups.

“I thought he was going to die,” Yelik said. And then he added, “Now I am nervous.”

Aska was stoic – more so than I’d been, definitely. His shins didn’t look bruised, although that didn’t mean anything; mine hadn’t visibly bruised either, but they ached terribly, some deeper, invisible bruise in the bone. More than the physical, though, he seemed shaken up by the flashbacks; after an hour or so he asked if I had any sleeping pills, because every time he shut his eyes he kept reliving the fall. I didn’t, but I gave him some advil and told him it should help, and apparently it did, because he said that he slept fine.

That night we enjoyed a final round of “Gulo gulo” over besbaramek. The next morning we set up a final bait station just above Yerlan and Jaksalak’s home. Aska hiked up with me to set the cameras, to prove that he was okay, and then rode his horse 40 km back to the town of Deluun. Watching him ride off so confidently, I took a deep breath and promised myself to stop being such a wimp about the horses henceforth. The enormous bruise on my butt, which I surreptitiously checked the day before when I was up in the forest alone, was starting to look less black and was fading to a violent dark purple. My wrist was still a problem, but I took the improvised cardboard brace off and decided to deal with it later, even though it still hurt to, say, hold a pen, braid my hair, or scratch my back. Horse danger was a fact of life in Mongolia and you either dealt with it or you were incapacitated by your need for safety.

The rest of us rode back to Deluun in a land rover. Over the winter, Aska would rebait the camera stations as needed, and Yelik would switch out the cards in December to see which stations were receiving wolverine visits. I was pretty sure that most of the bait would be devoured by foxes, but there were enough wolverine tracks to make me hopeful. Ultimately, we wanted to identify the best places to set up a trap or two for collaring, and, if we were very lucky, find places where multiple wolverines were visiting the cameras. The only thing to do now was wait, and head back to Khokh Serkh in hopes that we would capture that even more elusive animal, the snow leopard.